Everyone deserves access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation.

There is a broad consensus in the international development community that equity in the water and sanitation sector needs to be the focus of all efforts. This means prioritizing and reaching disadvantaged populations and ensuring equitable and inclusive water sanitation and hygiene outcomes. But countries are just not making the the right choices to prioritise equity to get us there. A number of UN and other international studies indicate that even with the spending that is occurring in the WASH sector those with disabilities, indigenous communities, poor local rural communities, and other members of marginalized populations like migrants are the ones that still significantly lack access to the essential services of water, sanitation and hygiene. This contrasts with significant progress in urban communities.

A 2019 study in Uganda conducted by Twaweza on assessing access to water and sanitation by household, including quality and barriers to access, found that there has been progress in the WASH sector for urban populations, 3 out of 4 Ugandans (75%) access water from an improved source including 19% have access to piped water. But progress in terms of access to piped water, between urban (42% piped) and rural (11% piped) areas, and poorer (8%) and wealthier (45%) households remains significant. In addition , households with one or more disabled members are less likely to have access to piped water than other households (12%, compared to 21%). The problems come down to the lack of water points (36%), the distance to water sources (27%) and dirty water (25%).

The big question is why. A 2018 report from UNICEF found that governments “need to better understand who is missing out on development and why.” A lack of data about marginalized groups access is one of the first challenges governments need to address. Despite Sustainable Development Goal 6, on Water and Sanitation adopted in 2015 that aims to ensure water and sanitation are available and sustainable for all, there is still a lack of data in this area of who are the most in need at the country level.

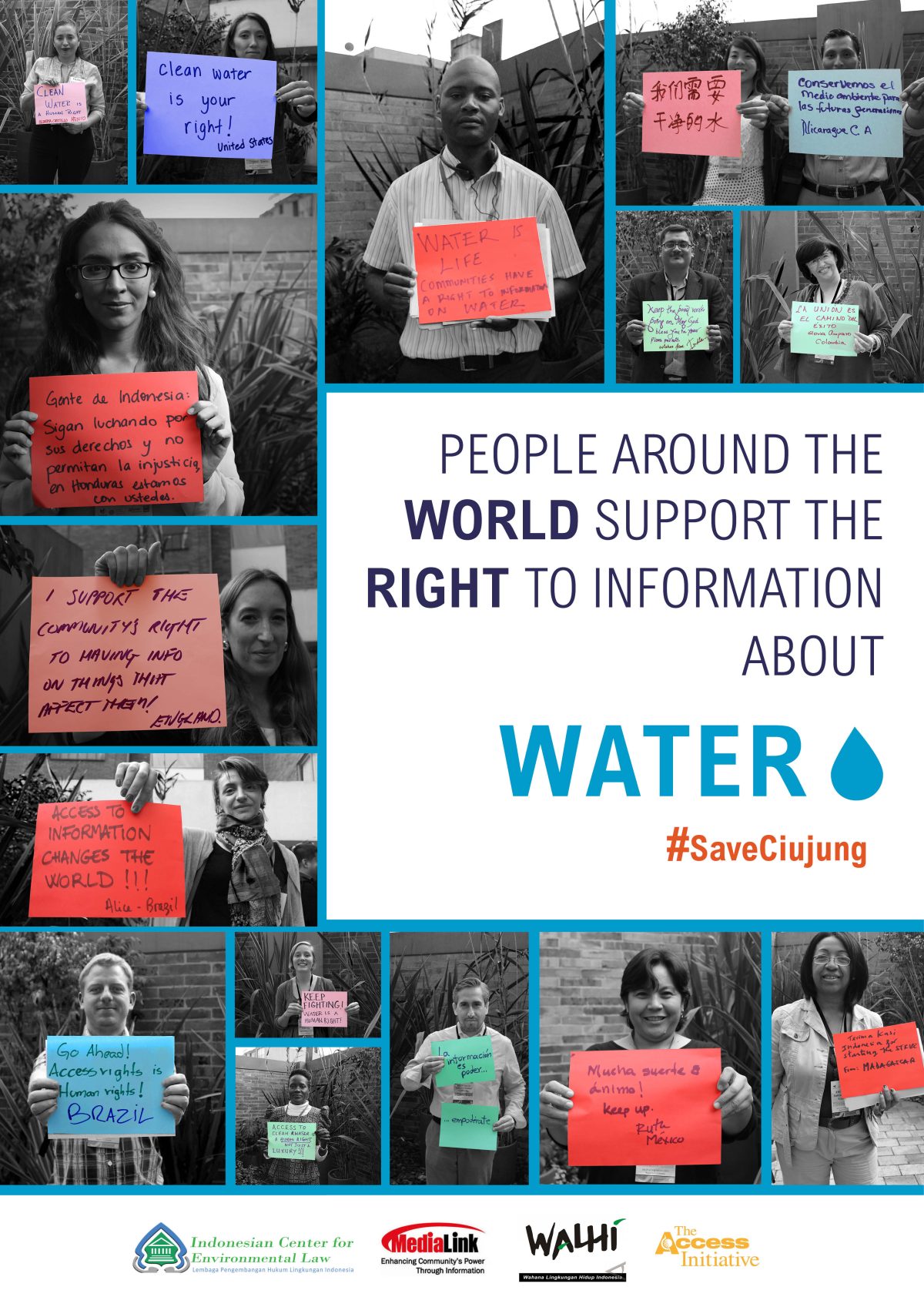

Open government principles could help change that. To improve WASH service, countries should commit to open government principles including on how they are setting priorities, spending their budgets, and using accountability measures to ensure WASH programming reaches the most vulnerable. Having commitments around open government principles can add a dimension of accountability around how government services will reach vulnerable populations. Commitments can be made through the Open Government Partnership a voluntary partnership where governments make new commitments on transparency, participatory mechanisms, and accountability. Within the OGP WRI, Foundation Avina, Stockholm International Water Institute, Water Integrity Network and have created a Water and Open Government Community of Practice which has finalized a Open Government Declaration focusing on water and sanitation. The Open Government Water and Sanitation Declaration is an international call to bring together water and open government reformers to mobilize ambitious action that strengthens implementation of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) service delivery. It outlines targeted recommendations that leverage transparency, participation and accountability that can be utilized through OGP and other WASH forums to increase collaboration and realize the human right to water and sanitation. The Declaration was created through an inclusive participatory process to bring the open government and water communities together on a concrete agenda to promote open government and WASH commitments through the Open Government Partnership to deliver on the needs of the most vulnerable for their basic rights to water and sanitation. The Declaration was drafted by a broad coalition of civil society and international organizations who acted as an advisory council including Article 19 – Yumna Ghani ;Transparency International – Donal O’Leary ; Akvo – Peter van der Linde ;Center for Regulation Policy and Governance – Mohamad Mova Al Afghani ;African Civil Society Network on Water and Sanitation (ANEW) – Sareen Malik ; Agua y Juventud – José Jorge Enríquez ; CLOCSAS – Jose Miguel Orellana ;Young Water Solutions – Antonella Vagliente ;CENAGRAP – Segundo Guaillas ; Inter-American Development Bank – Marcello Basani .

The Declaration was completed during the COVID- 19 Pandemic which highlights the critical importance of water for health and community safety. We invite individuals and organizations to endorse the Water and Open Government Declaration and help build a movement for open government action on WASH delivery challenges. For more information about the Declaration check out the launch video here and the Declaration in Spanish or English . Endorse the Declaration with the following links

Link for English – https://forms.gle/pFHNsfu2UsZticsc8 and Spanish Firme la DECLARACIÓN DE GOBIERNO ABIERTO Y AGUA Y SANEAMIENTO: Un llamado global para fortalecer la implementación de servicios de agua, saneamiento e higiene. (google.com) French https://forms.gle/H5s5rMAbqNoTHL8n9

Governments, Ministries , International Financial Organizations, and Water Utilities and civil society are invited to endorse the Declaration to support countries decision-making to be more transparent, enable inclusive participation in decision-making, improve accountability and ensure WASH services are gender- and socially inclusive. Inequity and intrinsic barriers will not just disappear by themselves, commitment to change will be crucial to ensure that vulnerable populations can receive adequate WASH services.