Countries made many national climate commitments as part of the Paris Agreement on climate change, which entered into force earlier this month. Now comes the hard part of implementing those commitments. The public can serve an invaluable watchdog role, holding governments accountable for following through on their targets and making sure climate action happens in a way that’s fair and inclusive. But first, the climate and open government communities will need to join forces.

Historically, open government and climate groups have worked in silos, operating in different forums, using different terminology and meeting with different stakeholders. Yet the NGOs, academics and other non-state actors focused on transparent governance and accountability are critically important in the climate arena, especially now that countries must address numerous governance hurdles, including the need for national level institutional coordination, capacity building and political buy-in. Bringing together the open government and climate communities offers an opportunity to develop new strategies that enhance accountable and inclusive climate policy decision-making.

Here are four areas where these communities can lean in together to ensure governments follow through on effective climate action:

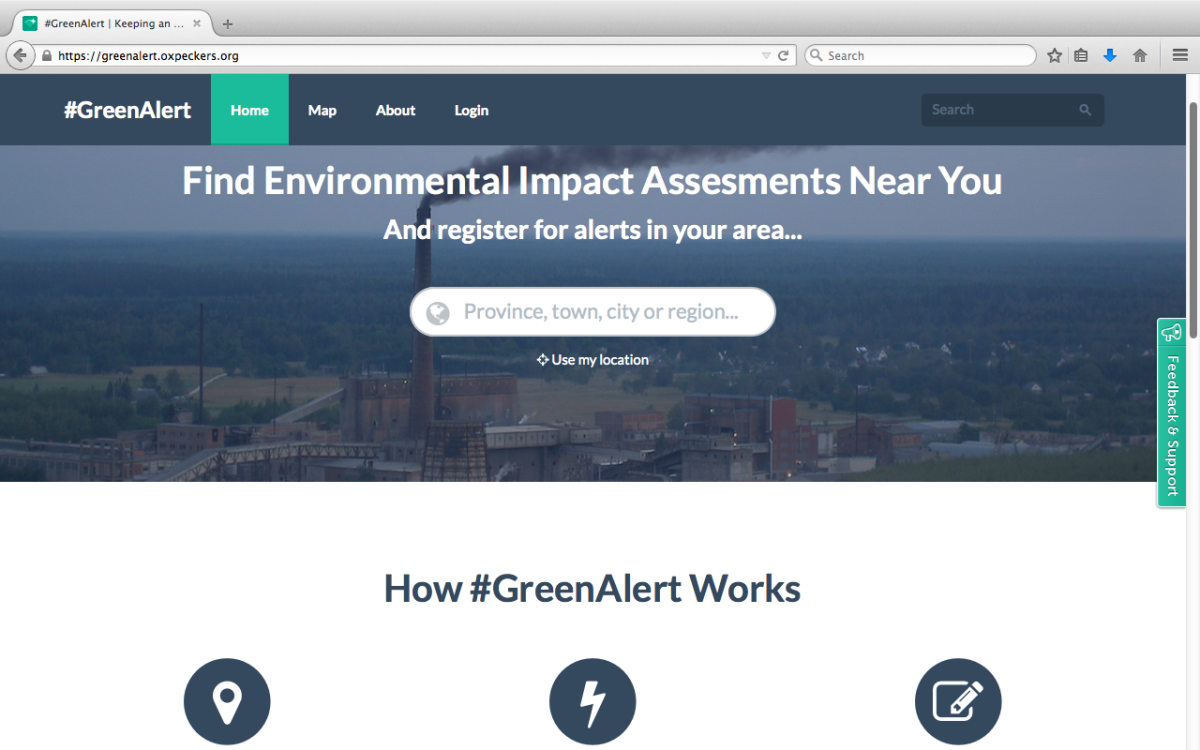

1) Expand access to climate data and information.

Open government and climate NGOs and local communities can expand the use of traditional transparency tools and processes such as Freedom of Information (FOI) laws, transparent budgeting, open data policies and public procurement to enhance open information on climate mitigation, adaptation and finance. For example, Transparencia Mexicana used Mexico’s Freedom of Information Law to collect data to map climate finance actors and the flow of finance in the country. This allows them to make specific recommendations on how to safeguard climate funds against corruption and ensure the money translates into real action on the ground.

Civil society NGOs can also provide alternatives to online portals to ensure information is actually reaching local communities. One group in Indonesia, Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Indonesia (YLKI), uses its weekly consumer radio show to provide a forum around electricity issues in Jakarta. This allows them to directly share information about public rights around electricity services, provide a forum to answer questions, and increase the ability of local residents to address grievances about power cuts and service reliability.

2) Promote inclusive and participatory climate policy development.

Civil society and community groups already play a crucial role in advocating for climate action and improving climate governance at the national and local levels, especially when it comes to safeguarding poor and vulnerable people, who often lack political voice. Public survey research has also found that people want civil society NGOs included in climate policymaking decisions, and believe the process is more legitimate when civil society is involved. Open government and climate civil society groups can use their links with local communities to strengthen the number and type of initiatives used to feed public input into wider policy debates and secure a seat for both men and women at the decision-making table. This can include mobilizing youth awareness, training indigenous leaders on proposed and negotiated climate change legislation and their rights around the principle of “free, prior, and informed consent,” or strengthening NGO participation in government-led roundtables on national climate change agendas.

3) Take legal action for stronger accountability.

Accountability at a national level can only be achieved if grievance mechanisms are in place to address a lack of transparency or public participation, or address the impact of projects and policies on individuals and communities. Civil society groups and individuals can use legal actions like climate litigation, petitions, administrative policy challenges and court cases at the national, regional or international levels to hold governments and businesses accountable for failing to effectively act on climate change. In the Netherlands, for example, the Hague District Court determined the country must further reduce CO2 emissions to adequately address the impacts of climate change and meet their obligation to protect people and the environment. The case was brought by the Urgenda Foundation, a Dutch NGO, and 886 individuals concerned about the country’s ongoing contribution to climate change.

4) Create new spaces for advocacy.

Bringing the climate and open government movements together allows civil society to tap new forums for securing momentum around climate policy implementation. For example, many civil society NGOs are highlighting the important connections between a strong Governance Goal 16 under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and strong water quality and climate change policies. WRI is hosting the sixth Global Gathering of The Access Initiative, called “Open Government for Climate Action,” organized in connection with the December Open Government Partnership Summit (OGP). This event will bring together leading thinkers in open government, open data and climate to exchange ideas on how civil society can best engage in implementing national climate policy.

The Gathering will also inform future open government commitments made by OGP member countries, including many of the countries responsible for the largest emissions of greenhouse gases, such as the EU, United States, Mexico, Indonesia and Brazil. The Gathering and Summit offer exciting opportunities to bring together the separate worlds of open government and climate. Together, they will help spur accountable and inclusive climate action that improves the lives of local communities.