By Elizabeth Moses and Elizabeth Wilkinson (Posted: March 8, 2016)

Women have a vital role in the conservation and management of sustainable ecosystems. The translation of access rights into stronger natural resource governance must include careful consideration of the impacts to the empowerment of women, the protection of their rights, and their meaningful participation in decision making. With growing momentum around multiple global initiatives such as the SDGs, Open Government Partnership and the Paris Agreements the ability to meaningful include women’s voices has become even more critical.

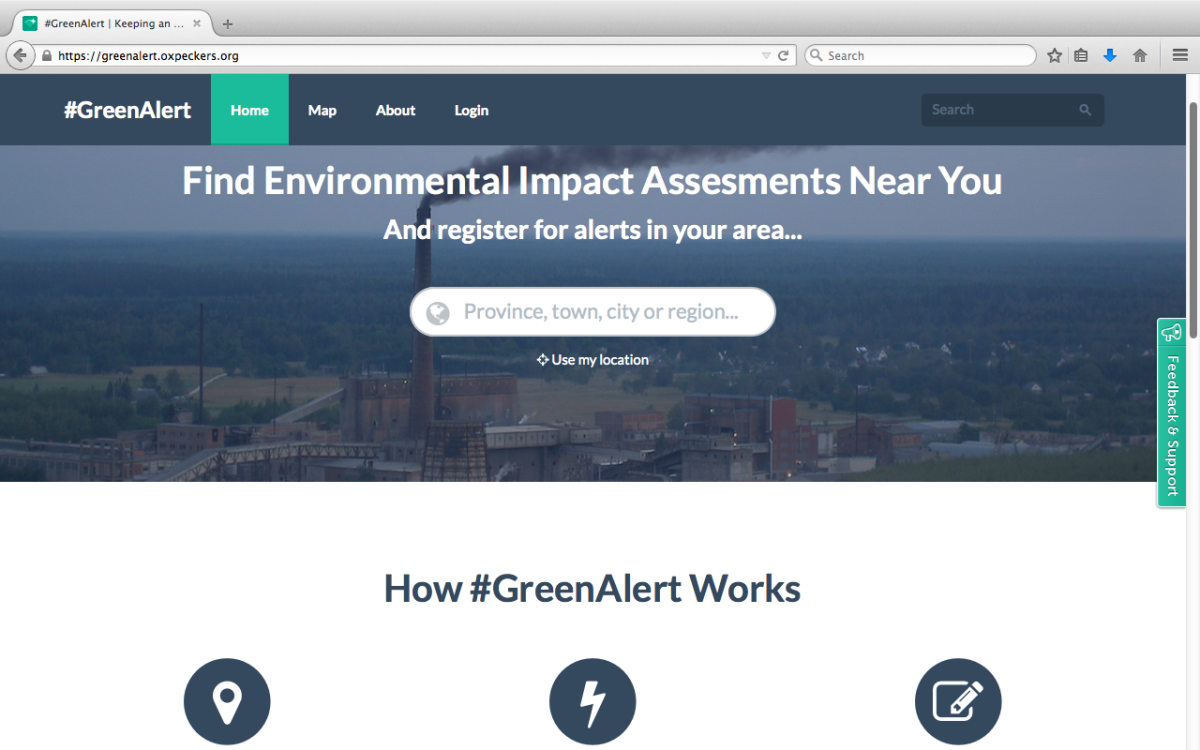

The Access Initiative (TAI) is a global network of diverse national and local partners working to strengthen access rights on a range of environmental sectors on the international, regional, and national stage. WRI’s Environmental Democracy Practice acts as Secretariat of TAI. This wide breadth means TAI can provide a unique forum for dialogue and exchange of ideas around gender and environmental democracy and use our platform as a catalyst for change.

In November of 2015 the TAI secretariat conducted a survey (found at http://www.accessinitiative.org/blog/2015/10/exploring-ways-…) of the members in its network to determine whether TAI would benefit from a more comprehensive gender integration strategy. Our goal was to use the survey results to identify new opportunities to work together and to support development of robust strategies that incorporate gender disaggregated data and help bring attention to the importance to the gendered dimensions of access rights. The survey was completed in December and a number of important findings were gathered from the responses received.

Strong Interest in Gender

There is high interest and a prevalence of gender-related projects within the network, although the majority of respondents have only recently begun to incorporate gender into their work. In fact over half (56%) of the respondents only have 0-5 years of experience working on gender issues.

Many TAI members emphasized that they are seeing overwhelming success with women’s participation in projects and to a lesser extent around economic empowerment and dialogue around women’s issues. Participation successes ranged from getting women together to discuss issues impacting them in Madagascar to actively having women participate on court cases in Argentina.

Challenges for Mainstreaming Gender

Yet major obstacles such as culture and marginalization still need to be overcome. This included overcoming difficult political and social climates around issues of gender and women’s empowerment. Other TAI members mentioned outside organizations and donors questioning their legitimacy to work on these issues and internal obstacles such as the lack of staff expertise on gender.

Almost all partners (65%) listed difficulty finding and receiving funding for gender-responsive projects. Reasons provided include a decrease in donors funding gender work, minimal focus on gender by partner organizations, and the lack of priority on gender issues in national government good governance programs or strategic plans.

The types of issues that women are facing in TAI countries are the typical issues being worked on in gender and development globally. Lack of education, participation, economic empowerment, health and reproductive issues, land grabs/property rights, public transportation access, climate change, and natural resource management and ownership were all mentioned as the major issues facing women.

But Many Opportunities to Continue Gendered Focus Work

TAI partners identified a wide range of local, national, and international opportunities for furthering work that responds to gender issues, including the SDGs, the Paris Climate Change agreement, and multiple in country and community initiatives but there was no major coalescence around what the priority gender issues are within the network. For example • In Bolivia, where violence against women is a major problem, they focus much of their work on the prevention of violence and reframing masculinity. • Other Latin American partners are interested in the impact of pesticides on reproductive health. • In Africa, many of the partners are working on women engaged in agriculture, and on economic empowerment.

The survey results clearly indicated members’ interest in working together to further a gender-responsive approach to our work. Respondents identified issues around fundraising assistance, donor identification and knowledge and information sharing as key areas where the Secretariat could better assist the members. A comprehensive overview of the TAI Survey can be found here (https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwL7hAAnUEy-TktJNHh5UUx6WHM… ).

Next Steps

Based on these findings, we confirm a widespread interest in strengthening TAI’s commitment to inclusive and empowering access rights and a need to support efforts to put this goal into practice. In response, the TAI Core team has agreed to form a TAI Gender Working Group led by Olimpia Castillo (http://www.comunicacionambiental.org.mx/contacto.html), Comunicación y Educación Ambiental, Mexico and Elizabeth Moses (http://www.wri.org/profile/elizabeth-moses), TAI Secretariat, WRI. The working group will finalize development of TAI’s gender strategy to provide an overarching framework for bringing a gender-responsive approach to our work and to define our next steps. This strategy will be rooted in the ideas taken from the survey and will focus on:

• Catalyzing changes in policy and practice through integration and transformative change. This requires removing gender biases from legal frameworks and ensuring that they are enforced, and the inclusion of actions to close gender-based gaps and disparities into policies, planning, and implementation that are sector specific.

• Building alliances both vertically and horizontally. Survey respondents emphasized the desire to collaborate with other organizations who are working on similar issues, particularly within their region. The goal of this objective will be to also expand the types and number of groups in the TAI network and build credible multi-stakeholder coalitions.

• Making the case through evidence-based advocacy and research. There is a lack of sex-disaggregated data and this goal hopes to produce such information, as well as to promote gender-inclusive participation.

• Building network capacity. Capacity building will focus on organizing and collaborating nationally, internationally, internally and across TAI’s network, to strengthen gender-inclusive stakeholder engagement.

TAI is excited to move forward. We hope sharing our learning process and plans for action will inspire other environmental networks and organizations to consider how gender should be priority in their work as well.