Will African communities ever become the beneficiaries and owners of their mineral resources, asks Tholakele Nene

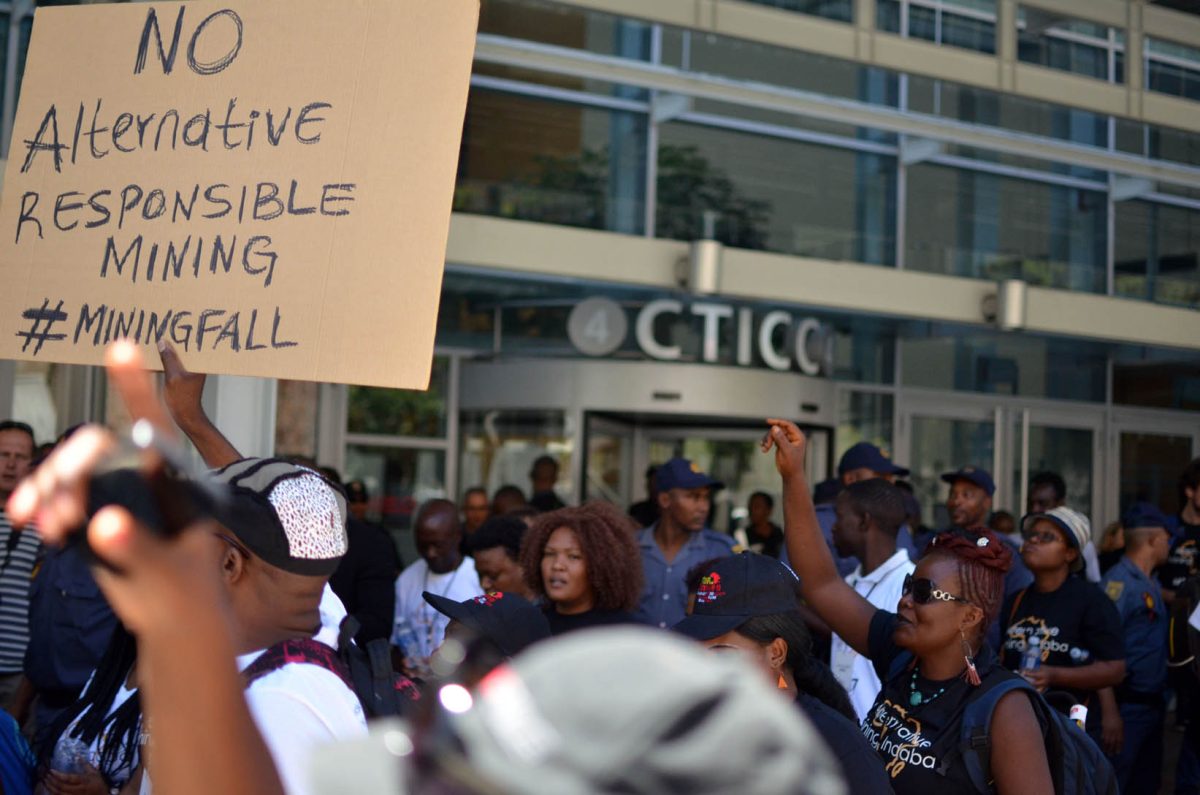

The question set the tone of the 2018 Alternative Mining Indaba, held in Cape Town in February, under the theme “Making Natural Resources Work for the People: Towards Just Legal, Policy and Institutional Reforms”.

The more I listened to regional stories from activists in our neighbouring countries talking about how decades of mining policy development still leaves Africa’s people sidelined when it comes to benefit sharing and access to information, the more I realised the importance of fighting for mandatory disclosure.

Dr Ayoa Graham, executive director of the Third World Network in Ghana, spoke about how extractive laws in Africa are “defective” when it comes to implementation, monitoring and evaluation. There is an absence of cost-benefit analysis, he said, and no research about what minerals we have, what they are worth and how Africa can benefit from its own resources.

Graham emphasised the importance for communities of understanding how the revenue generated from the mining of minerals is used, and where it is being used.

“In the absence of cost-benefit analysis, communities are left to deal with mining companies for compensation. We should be moving to a regime where the state should take responsibility for the compensation of people and treat them as part-owners of the resources”, he said.

Lack of transparency

In the South African context #MineAlert has documented complaints from mining-affected communities that the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of various mining laws by the Department of Mineral Resources is near absent.

We have interviewed communities in coal-rich Mpumalanga to find out whether Social and Labour Plans (SLP) have facilitated benefit sharing and found there are still community members who had no idea of what an SLP is, let alone where to get a copy that they can use to hold a mine to book on promises made and not delivered during public consultation processes.

The argument is that, if mining companies are not voluntarily sharing crucial documents such as financial reports and SLPs with the general public, they not only take away the public’s right to access information that could assist communities make informed decisions and benefit from profits made from Africa’s minerals, they also reduce the chances of being held to account by limiting transparency. This makes it easier for mining companies to dig up the minerals and take the lion’s share of the profit, leaving the breadcrumbs for communities to wrangle over.

Mandatory disclosure

“In South Africa the current transparency regime regulating the private sector, including the extractives industry, is focused largely on enhancing information disclosure to shareholders or investors, rather than more broadly to all stakeholders which will include the public and local communities,” found a research report on the legislative and regulatory regime, published by the Open Society Foundation-South Africa (OSF-SA).

The research investigated the limitations and prospects of various institutions that oversee the extractives industry, including their powers to enforce compliance. It also analysed 30 laws, including the Promotion of Access to Information Act and the Mineral (PAIA) and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), which are often seen as the cornerstone of transparency and justice in the extractives industry.

“There were very limited disclosure rules relating to ownership, operational and financial information,” the report concludes.

The MPRDA, for instance, provides that the holder of a mining right or mining permit must, at the registered office or place of business of such holder, keep proper records of mining activities and proper financial records in connection with these activities. Furthermore, the holder needs to submit records such as progress reports to the regional manager.

Section 30 of the Act says that this information may be shared with any persons as part of exercising the right to information. However, the Act prohibits disclosure where the information has been supplied in confidence.

The difficulty of accessing crucial information on extractives was highlighted by Publish What You Pay South Africa in a case study on Sedibeng Iron Ore. The organisation is working on a mandatory disclosure campaign that would see stronger legislation promoting public disclosure of mining documents such as financial reports.

International best practice

In 2017 Canada implemented an Extractives Sector Transparency Measures Act that requires all Canadian registered and listed extractives companies to disclose payments to governments in Canada and abroad. This has led to hundreds of companies publicly disclosing reports detailing payments to government by Canadian extractives companies.

Is it not time to look at similar legislation in South Africa?

Tholakele Nene is an Associate of Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and manager of the #MineAlert app, which allows users to track and share mining applications and licences across South Africa